|

|

|

Промышленный лизинг

Методички

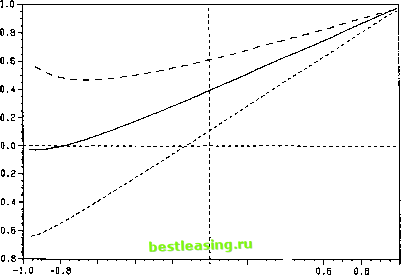

-0.6 -0.4 -0.2 0.0 0.2 Correlation of the supply increments p г 0.4 Figure 5 The unconditional correlation in price changes corr(i 2 - Plt и - P2 H0), as a function of p, the correlation between supply increments xt and JCj. The solid line represents the case in which V\ = V\ = 226, the short-dashed line the case in which V\ = 113 and V\ = 226, and the long-dashed line the case in which V\ = 226 and V\ = 113. The values of the remaining parameters are set equal to the base values shown in Section A of Appendix С rium, weak-form efficient? Not surprisingly, the answer depends on the definition of efficiency. Fama (1970, 1976) defines a market as weak-form efficient if current prices fully reflect historical market statistics, including past prices. Here, fully reflect is taken to mean that conditioning on past and current prices provides the same set of beliefs as conditioning on only current price. The analysis of Section 2 demonstrates that, in this market, adding historical price to an investors information set generally changes beliefs and investment policies. Thus, this market is inefficient in Famas sense, even though the current price is determined by investors who rationally use past price in setting their demands. Rubinsteins (1975) and Beavers (1980) definitions require that publishing the information not change equilibrium prices. Rubinsteins notion allows one to ask only if the market is efficient with respect to all information, so it is of little interest to this discussion. Beaver provides a definition of market efficiency with respect to an information set that might be the information contained in historical prices. One finds that the noisy rational expectations equilibrium discussed here is weak-form efficient in Beavers sense. But this is not surprising. Any perfectly competitive market in which the individuals have recall of past prices is weak-form efficient in Beavers sense. Revelation of past prices does not change the current price or the distribution of future prices because historical prices are, by assumption, commonly known in equilibrium.12 Verrecchia (1982) defines a market to be efficient if, conditional on observation of the noise in the market, for example, xx and x2, the price is no less efficient an estimator of the value of interest, for example, u} than the estimator available to any single trader. Each of the prices in the rational expectations equilibrium developed here reveals и perfectly when Xi and x2 are known. Hence, this market is efficient in this sense. A market is efficient with respect to an information set in the sense of Latham (1986) if publishing that information does not change either prices or an individuals optimal policy. Considering the technical analyst of Section 2, one concludes that the noisy rational expectations equilibrium is not weak-form efficient in this sense. Adding historical price Px to this individuals information set, containing only current price P2 and prior information S0, alters the optimal demand. Discussions of weak-form efficiency in modern investment textbooks often include statements such as the following: If the market is weak-form efficient, then current prices fully reflect the information in historical levels of prices and volumes of trade. Technical analysis has no value. 13 Such a statement is, in part, a warning to the reader to be skeptical of those offering investment advice based solely on naive analysis of historical data. Given the empirical work examining some (historically) popular forms of technical analysis, the advice apparently is well taken.14 What is not clear from textbook discussions of weak-form efficiency is whether the statement that technical analysis has no value is an implication, derived by logical reasoning, of the assumption that the market is weak-form efficient, or whether it is the defining characteristic of weak-form efficiency. If the latter is assumed, then the market discussed in this work is not weak-form efficient. Technical analysis does have value. Alternatively, in the case that technical analysis has no value is an implication of market efficiency, this work demonstrates that this inference may be unwarranted, given a definition under which the noisy rational expectations equilibrium is efficient. 4. Summary and Discussion of a Possible Extension The noisy rational expectations model of Diamond and Verrecchia (1981) and Hellwig (1980) has been extended to two periods. It has been shown that ТА has value in every myopic-investor economy. From the numerical analysis of the rational-investor economy, one finds that the second-period 12 An alternative to the market studied here has historical prices excluded from investors information sets. Such an alternative is not efficient in Beavers sense; the addition of historical price information changes current prices. 13 Examples of such statements include Jones (1985, p. 433), Reilly (1985, p. 197), and Haugen (1986, p. 469). 14 See, for example, Alexander (1964), Fama and Blume (1966), Jensen (1967), and Seelenfreund et al. (1968). A caveat is that these are generally studies of unconditional moments; see Section 3. price is dominated as an informative source by a weighted average of the first- and second-period prices. Investors use the historical price in determining time 2 demands because the current price does not reveal all publicly available information provided by price histories, that is, investors use technical analysis to their benefit. Treynor and Ferguson (1985) study the dual of the problem presented here. The asserted usefulness of their methodology is based on the assumption that a trader knows the exogenously determined effect of a particular news item on an asset price given that the market has received the information. They examine the usefulness of past prices in estimating the time the news is disseminated. In their setting, a trader receiving the information privately must decide how to act. If he receives the information before the market, then he establishes the appropriate position to profit from the change in price that is forthcoming when the market becomes informed. If he receives the information after the market, then he does not act. The trader uses past prices to assess the probability that he has received information before the market. The dynamic rational expectations equilibrium of plans, prices, and price conjectures studied here assumes that each trader knows the time of the release of private information (signals) to other traders but does not know the values of the signals. Past price levels, then, enable traders to make more precise inferences about the signals. A logical, but not straightforward, extension of the present model allows the release time of the private information to be stochastic and heterogeneous across investors. For example, one might posit a subset of investors who are, with some positive probability, informed of, say, a firms earnings prior to the public announcement of the earnings. In this case, the uninformed investors use historical price levels to forecast jointly the timing of the public announcement and the level of earnings.15 In such a model, unlike that of Treynor and Ferguson, the effect of information on the price is endogenous. A caveat regarding the implementation of such a methodology is that the joint statistical behavior of price levels and earnings levels must be well understood. How well this is possible is, of course, an empirical question. Appendix A: The Equilibrium Price and Demand Functions It is shown in this appendix that the linear price conjectures (5) lead to 1) linear demand functions, Equations (6) or, alternatively, Equations (9) and 2) linear equilibrium price functions (8). It is also shown that conditions (10) are necessary for ТА to have no value. Throughout, it is assumed that h0, slt s2, Vl9 V2, and Я are each greater than zero; that p < 1; that the price coefficients yx and 82 are nonzero; and that the values Gu and G12 (see Proposition A2) exist and are nonzero. 15 Beaver, Lambert and Morse (1980) propose forming expectations regarding accounting earnings from stock price movements. However, they do not consider the possibility of serial correlation in price changes. 1 2 3 4 [ 5 ] 6 7 8 |