|

|

|

Промышленный лизинг

Методички

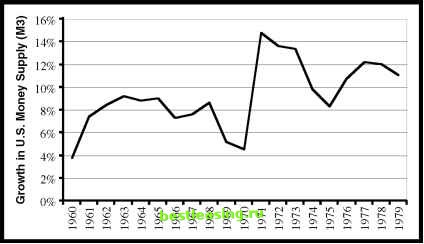

professors Ernst Fehr and Jean-Robert Tyran indicate that people do exhibit money illusion.12 A more mundane version of money illusion is the tendency for people to set watches and clocks a few minutes fast. The clock on my computer has been six minutes fast for years. If I were completely rational, I would immediately know the real time. Even after years, however, my lizard brain is still fooled by my fast clock. While I can rapidly calculate the correct time, my first glance takes the clock at face value. Consequently, I get out the door a little sooner than I would with a clock with the right time. Money illusion is one reason economists believe that some inflation is good. Inflation allows the adjustment of prices without triggering anyones emotional stand against getting a worse deal. For example, increased competition from China might cause the appropriate wage for U.S. textile workers to go down. This real-wage drop can occur either through an actual pay cut (which is likely to be resisted) or through a wage increase that is less than the rate of inflation. The true economic impact is the same in both cases, but one is more palatable. Wage rigidity appears to hold outside the laboratory as well, and some believe it was an important source of the extremely high unemployment rate during the Great Depression.13 Because of money illusion and deflation, some scholars argue that Depression wages did not fall to levels low enough to induce employers to hire more workers. This Goldilocks view of inflation has been studied extensively by a large number of economists.14 In 1996, Larry Summers gave a talk on his views on the optimal inflation rate. Larry Summers is currently the president of Harvard University, and although still quite young, was a tenured economics professor at Harvard before holding a variety of nonacademic positions, including Secretary of the Treasury. In his discussion, he summarizes this sticky wage situation as follows: You cant get real-wage reductions without nominal wage cuts, making it harder to get the needed labor market adjustments. For this and other reasons, Professor Summers concludes that an inflation rate of 1 to 3% looks about right. 15 Yogi Berra and Milton Friedman Share a Pizza Where do we stand in our monetary journey? First, we have learned that money is a financial tool invented to lubricate the economy. Without money we would be forced to use inefficient and complex simultaneous exchange as in the kidney transplantation market. Second, we determined the attributes of ideal forms of money, which helps us understand the progression of types of money. Third, we have learned the Goldilocks rule that some inflation, at a low rate, is just right. A mystery remains, however, and it is the one that worried me in the 1970s. All of our knowledge about money and inflation is great, but what is the use if inflation is an uncontrollable monster capable of toppling presidents and destroying societies? Knowing the enemy may have some benefits, but it would be much better if that enemy could be shackled. The real mystery of inflation is that there is any mystery at all. There is no magic behind the cause and control of inflation. In The Wizard of Oz, the magic of the land is revealed when Dorothy pays attention to the man behind the curtain. Similarly, there are people who determine the inflation rate. Far from being an uncontrollable beast, inflation is a tame dog both created and completely controlled by monetary authorities. Milton Friedman appropriately gets credit for the academic understanding of inflation. As in many other areas, however, Yogi Berra captured its essence without a Ph.D. in economics. When asked how many pieces he wanted a pizza cut into, Berra replied by saying, Just four, Im on a diet. (Whether he actually made this joke is subject to dispute. Berra claims to be misquoted frequently. He coauthored a book titled I Really Didnt Say Everything I Said.) Regardless of its origin, the joke recognizes an obvious truth. A pizza contains the same number of calories regardless of how it is divided. Thus, the choice of the number of slices merely determines the size of each slice, not the size of the overall pizza. Professor Friedman made the same discovery when it comes to the value of money. The decision on how much money to create doesnt have much effect on the overall size of the economy, but it does have an enormous effect on the value of money. He wrote, Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. 16 When the amount of money is increased, the result is inflation. Inflation destroyed the value of seashells in Papua New Guinea. When their money supply increased because of the importation of planeloads of seashells, the value of each seashell decreased. Similarly, the German hyperinflation was caused by a massive increase in the supply of German marks. Inflation is simple. When more money is created, the value of each piece of money declines. That is inflation. What about the U.S. inflation of the 1970s? I was particularly scared by news reports that suggested inflation was some mysterious force. As Figure 5.2 shows, this inflation was not mysterious at all. It was, to quote Milton Friedman, a monetary phenomenon. The inflation of the 1970s was caused by a rapid growth in the money supply. Just as there is no mystery (to those in the know) for the cause of inflation, there is no mystery for its cure.  FIGURE 5.2 1970s U.S. Inflation Was Created by Loose Money Source: U.S. Federal Reserve 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 [ 35 ] 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 |