|

|

|

Промышленный лизинг

Методички

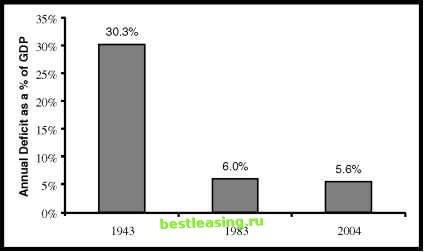

FIGURE 7.4 The U.S. Annual Deficit Is below Historical Highs Sources: Office of Management and Budget, Congressional Budget Office overall economy! The CBO projects that over the next decade, 2004 will have the largest deficit when measured against the size of the economy. The projected 2004 figure of 5.6% of GDP is smaller than the 6.0% of GDP figure that occurred in 1983 (the largest of the Reagan era deficits). Is it possible to have $500 billion deficits as far as the eye can see without harming the economy? The answer appears to be a resounding yes. In fact, throughout the early 1980s, the United States ran large deficits every year while the economy prospered. Specifically, in spite of large deficits, interest rates fell during the 1980s. While we cant know what would have happened in the 1980s with smaller deficits, the U.S. economy seems able to handle deficits in the range of 5% of the size of its economy. So what is the likely effect of deficits on interest rates? With current projections, the deficits look to provide some upward pressure on interest rates but with no cause for panic. The projected U.S. federal deficits and debt are well within historic ranges. The key will be to watch as the deficit and debt figures change. If annual deficits and cumulative debt swell beyond current projections, they could cause interest rates to rise substantially. Three Ways to Lose Money in Ultra-Safe U.S. Government Bonds The federal government deficit, as currently projected, does not seem to spell doom for bonds. Those who argue that the deficit will cause problems have been making their bearish case for decades. In fact, Professor Tobins quote regarding the crowding out effect was made in 1986. Eighteen years later, Alan Greenspan said, One issue that concerns most analysts, especially in the context of a widening structural federal deficit, is inadequate national saving. 5 Those who fear that the large U.S. federal deficits will eat up all the available savings might eventually be proven right, but there is no evidence of a problem yet. Even though U.S. government bonds are among the safest investments in the world and there is no imminent risk from deficits, there are three ways investors can lose money: (1) You never get your money back, (2) you get worthless money back, or (3) you get much less money back than alternative investments. Bond Risk #1: Government Default The most extreme risk is that the U.S. government defaults on its bonds. Many corporations and other countries have defaulted on their bonds. It is almost impossible to imagine the U.S. federal government defaulting. In the most extreme circumstances, annual U.S. government deficits could reach trillions of dollars. Even in such circumstances, the government has unlimited ability to create dollars so there is essentially no risk of default. A U.S. government default is almost impossible. Those who worry about such a default ought to be investing heavily in items such as guns and food. I am not saying that it is impossible for the U.S. government to default on its bonds, just that this is extremely unlikely, and if it happens we will have much more to worry about than our investments. Bond Risk #2: Inflation The second risk to bondholders is that they will be repaid but that the dollars they are repaid with might be able to buy very little. On this subject, the science fiction legend Robert Heinlein (author of Starship Troopers, Stranger in a Strange Land, and many other classics) wrote, $100 placed at 7 percent interest compounded quarterly for 200 years will increase to more than $100,000,000-by which time it will be worth nothing. We already covered the risk of repayment with worthless dollars in the inflation discussion. As of right now, there is no sign of dangerous levels of inflation in the United States. Nevertheless, the risk exists and is one of the most serious risks for bondholders. In most circumstances the interest rate on government bonds exceeds the inflation rate. While this has almost always been the case in the United States, the amount of cushion-the difference between interest rates and inflation-has varied dramatically. Figure 7.5 shows the interest rate on the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond minus the rate of inflation. The extra return on bonds above inflation has been decreasing for the last 20 years. The 1983 bond investor received 7% above inflation while the 2003 investor received only 1% above inflation. In comparison to current inflation, bond buyers today are getting the worst deal they have had in decades. Bond Risk #3: Opportunity Cost In 1989, I was the chief financial officer of Progenics Pharmaceuticals, a start-up biotech company (now publicly traded with the stock symbol PGNX). For no good reason related to my job, I wrote an analysis of the RJR-Nabisco leveraged buyout. The Wall Street Journal published a short version of my analysis as an editorial.6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 [ 51 ] 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 |