|

|

|

Промышленный лизинг

Методички

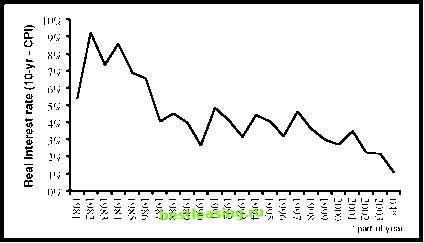

FIGURE 7.5 Interest Rates Adjusted for Inflation Are Extremely Low Source: Federal Reserve, Bureau of Labor Statistics One of the consequences of this article was an invitation to give my first lecture at Harvard. I was honored by the request so I flew to Cambridge to present my analysis. How did my first Harvard lecture go? The short answer is that it went amazingly poorly. Early in the lecture, I asserted that RJR-Nabisco bondholders had lost $1 billion because of the leveraged buyout. My calculation simply added up the loss on all RJR-Nabisco bonds as quoted on bond markets on the day the deal was announced. (These bonds traded actively so it was easy to get an accurate measure of how much the price dropped because of the buyout announcement.) A student objected by saying that the bondholders had lost nothing. She argued that the RJR-Nabisco bondholders were still going to get all their money back. Accordingly, she said that the current price of the bonds was irrelevant. I tried to argue against this view, but it was shared by most of the students. After about 20 minutes of incoherent verbal flailing, the professor had to intervene and say, Please, lets just assume that Terry is right and move on. This intervention allowed the lecture to continue, but obviously I had lost all credibility. Lets view this issue in the context of a $1,000 dollar investment into a 10-year U.S. Treasury bond. Assume that the bond is bought with an interest rate of 4%. The purchaser gives the government $1,000. In return the government promises to pay $40 a year for 10 years, plus return the original $1,000 at the end of the tenth year. Now lets consider what would happen if, soon after the purchase, interest rates on 10-year treasuries jumped from 4% to 6%. What would happen to our investor? The investor owns a bond that still promises to pay $40 a year for 10 years and to return the $1,000 upon maturity. From this perspective, the bondholder doesnt appear to have lost any money (this is the students argument from my lecture). On the other hand, the rise in interest rates means that the market price of the bond would have dropped by $150. So how much money would our bondholder lose? Is it $0 or $150 or something else? The economists answer is that the bondholder would lose the full $150 even if the government makes all the payments as promised. Where does the loss come from? The loss is caused by the change in the opportunity cost. By investing at 4%, the bondholder has lost the opportunity to earn 6% on the $1,000. And these are not simply losses on paper, these are real dollars that the investor could have in his pocket but never will. In my first Harvard lecture, and many since then, I have learned that opportunity cost is a difficult concept to grasp. Even highly trained people who understand the idea tend to overlook opportunity costs. While the opportunity cost in financial terms is often misunderstood, in other areas of life it is clear. A famous-and almost certainly fake- wedding toast goes as follows: Sometimes at rare moments in human history, two people meet who are meant to be together forever. When such romantic lightening strikes, I hope that the bride and groom have the strength to say, I am sorry, Im already married. For those who are unwilling to divorce, the opportunity cost of marriage is the forgone opportunities with other potential mates. A similar theme is revealed in stories of a mythical culture where women were allowed to have up to three husbands, but where divorce was banned. It was said that women in this culture almost never had a third husband, and when they did, he tended to be extremely handsome. By some calculations, the third husband has the highest opportunity cost in this marriage system because he rules out all future possibilities. So the bondholder who locks in a 4% interest rate for 10 years loses when the world changes to provide opportunities for 6% investments. How Low Can Interest Rates Go? U.S. bonds have had a 20-year run. When will interest rates begin to rise thus ending the bull market in bonds? Predictions, particularly of the future, are tough. (Economists have a nearly unblemished record for predicting the past.) The most famous wrong prediction of an economist is probably Yale Professor Irving Fishers quote that, Stocks have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau. Professor Fisher made this sanguine statement in October 1929 just before the stock market collapsed by 90% and the Great Depression began. Professor Fisher was, by some accounts, the worlds most famous economist and he made his remarks at precisely the wrong time. This is amazing, but not too different from the record of many economists. One of my neighbors is a meteorologist (and dont call her a weather lady) for one of the Boston TV networks. Shes a bit of a celebrity in the area. I see her from time to time in our buildings elevator, and my running joke with her has two themes (neither of them are at all funny). First, I blame her for bad weather and thank her for the occasional nice day. Second, I tease her for forecasts that often miss the mark. Actually, I used 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 [ 52 ] 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 |