|

|

|

Промышленный лизинг

Методички

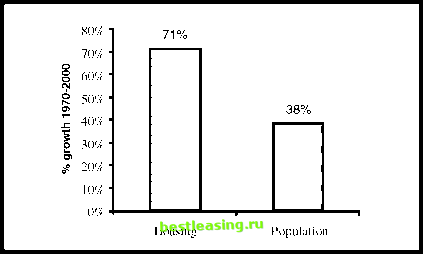

Clue #2: Housing Supply Has Grown Faster Than Housing Demand Economists are odd people in many ways. In addition to using the words supply and demand far more frequently than normal humans, we also spend a lot of time thinking about elasticity. As I found out in college, the abstract concept of elasticity can make the difference between wealth and poverty. Once a house has been built, it is not particularly easy to convert it to something else. Thus the supply of real estate is relatively inelastic. That means that the supply of housing changes only slowly. In contrast, something that is elastic can respond quickly to changes. What about housing demand? Barring some sort of tragedy, the number of people who need housing is also unlikely to change quickly. Does this mean that the demand for housing is also inelastic? No. Housing demand fluctuates far more rapidly than population. In tough times, people are remarkably flexible in their living arrangements. A recent college graduate, for example, with a good job cant imagine living at home. If unemployed, however, the same person becomes much more tolerant of her or his parents. In good times, therefore, demand for housing rises far more than population growth, and in bad times, people find ways to economize. Thus the housing market is characterized by inelastic supply and relatively elastic demand. So what? These sorts of markets have the interesting characteristic that price can change very rapidly. I learned this lesson when I was in college at the University of Michigan. Doug, the millionaire surfer, made a good living each Saturday scalping tickets at football games. My friend Scott and I decided to get some of this easy money. We hit upon the following strategy. Go to the student dormitories farthest from the stadium. Find students groggy from Friday night drinking and offer to buy their tickets for $1. Then ride our bicycles down to the stadium, sell the tickets for more, and collect our profits. We did this one bright Saturday morning and managed to make about $100 in a couple of hours. I remember our first sale. A couple was walking away from a BMW. I approached the man and asked if he needed tickets. He asked, How much? Scott responded with face value of $12. The man instantly agreed, and we had $22 in profit! The following Saturday, Scott and I were up early aggressively buying tickets. Buoyed by our success, we purchased more than 60 tickets, each for $1. As we rode our bikes to the stadium, however, we saw people offering to sell huge batches of tickets. We soon began selling tickets as fast as possible. The going prices started low and then plummeted. One buyer wanted six tickets. I offered six for $0.25 each. A competing scalper undercut me by offering all six tickets for a total of $1. Scott and I lost almost all of our investment. What happened? We learned that like housing, football games have inelastic supply and elastic demand. While both games that we worked were against similar quality opponents, the forecast predicted rain on the second Saturday. The supply of tickets was a constant of just more than 100,000 seats (the University of Michigans stadium is known as the big house ), but demand was slightly lower the second week. In markets with inelastic supply and elastic demand, prices can move very rapidly. As game time approaches there are either more buyers or more sellers. A relatively small shift in demand makes the difference between too many buyers and too few. This translates into the difference between high ticket prices and almost free tickets. On our second weekend of ticket scalping, Scott and I ended up throwing away dozens of tickets. The housing market has inelastic supply and relatively elastic demand. There is no equivalent of kickoff time when supply becomes worthless so the rental effects are not as extreme. Nevertheless, the real estate market is subject to relatively large changes in rents for relatively small changes in demand. Importantly, the supply of U.S. housing has been growing far more rapidly than the population. Figure 9.3 shows the relative growth between the 1970 and 2000 census. Over the last three decades, the growth in housing units in the United States has exceeded the growth in population. As discussed, this does not imply disaster. Over this time period, the United States has become far richer. As we have become richer, it is reasonable to expect that we would have more houses. Nevertheless, the fact that supply has grown so much more than population is a clue. If times get tougher, it is possible that demand for housing could drop enough to put significant pressure on prices. Clue #3: Vacancies Are on the Rise For the next clue, Figure 9.4 shows the U.S. rental vacancy rate. The U.S. residential rental vacancy rate is at the highest level on record. This is obviously good news for renters who have more power in their negotiations with landlords. On the other hand it is unambiguously  FIGURE 9.3 U.S. Housing Supply Has Grown Faster Than the Population Source: U.S. Census Bureau 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 [ 70 ] 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 |